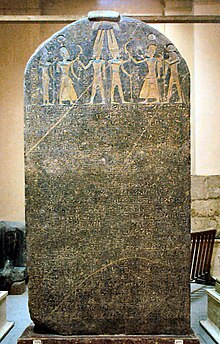

Merneptah Stele

Ang Merneptah Stele na tinatawag ring Israel Stele o Pagwawaging Stele ni Merneptah ay isang inskripisyon ng paraon na si Merneptah na naghari noong 1213–1203 BCE. Ito ay natuklasan ni Flinders Petrie sa Thebes noong 1896 at nasa it Museong Ehipsiyo sa Cairo.[1][2]

| Merneptah Stele | |

|---|---|

The stele in 2003 | |

| Paglalarawan | |

| Materyal | Granite |

| Pagsulat | Ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs |

| Petsa | |

| Ginawa | c. 1208 BCE |

| Pagkakatuklas | |

| Natuklasan | 1896 Thebes, Egypt 25°43′14″N 32°36′37″E / 25.72056°N 32.61028°E |

| Nakatuklas | Flinders Petrie |

| Kasalukuyan | |

| Nasa | Egyptian Museum, Cairo |

| Pagkakilanlan | JE 31408 |

| Kultura | |

| Panahon | Iron Age |

The Merneptah Stele was discovered in Thebes and is currently housed in Cairo, Egypt | |

Ang stela ay isang salaysay sa pagwawagi ni Merneptah laban sa mga sinaunang Libyan at mga kaalyado nito. Ang huling tatlong 28 linya ay nauukol sa isang hiwalay na kampanya sa Canaan na naging bahagi sa panahong ito ng Ehipto. Ito ay tinatawag minsang "Israel Stele" dahil ang Yis'rir ayon sa karamihan ng mga iskolar ay tumutukoy sa mga Sinaunang Israelita ngunit may ibang mga iskolar na tutol dito.[3]Ang stele ay kumakatawan sa pinakamaagang reperensiya sa mga taong Yisrir o mga taong Israel.[4] Ito ang apat sa kilalang mga inskripsiyon sa panahong Bakal na nagbabanggit sa mga Israelita kasama ng Mesha Stele, Tel Dan Stele, at Mga Monolitang Kurkh.[5][6][7] Consequently, some consider the Merneptah Stele to be Petrie's most famous discovery,[8]

Linyang 26–28

baguhinAng mga prinsipe ay nagpatirapa na nagsasabing "Kapayapaan!"

Walang nagtaas ng kanyang ulo sa mga Siyam na Busog

Ngayon ang Tehenu (Libya) ay nawasak,

Ang Hatti ay pinayapa;

Ang Canaan ay kinubkob sa bawat uri ng kaabahan:

Ang Ashkelon ay natalo;

Ang Gezer ay nabihag;

Ang Yano'am ay ginawang naglaho.

Ang Yisrir (Israel) ay nasira at kanyang binhi ay wala;

Ang Hurru ay naging balo dahils a Ehipto.

Ang siyan na busog sa katagang Ehipsiypo ay tumutukoy sa kanilang mga kaaway.[10]Ang Hatti at Ḫurru ay mga Levantino, ang Canaan at Israel ay mas maliit na unit at ang Ashkelon, Gezer at Yanoam ay mga siyudad sa loob ng rehiyon. Ang mga entidad na ito ay bumagsak kay Merneptah.[11]

|

|

|

|

| |||||||||||||||||||

| ysrỉꜣr | fk.t | bn | pr.t | =f | |||||||||||||||||||

| Yisrir (Israel) | Tapon | [negatibo] | binhi/butil | niya/nito |

Mga sanggunian

baguhin- ↑ Drower 1985, p. 221.

- ↑ Redmount 2001, pp. 71–72, 97.

- ↑ Kenton L. Sparks (1998). Ethnicity and Identity in Ancient Israel: Prolegomena to the Study of Ethnic Sentiments and Their Expression in the Hebrew Bible. Eisenbrauns. pp. 96–. ISBN 978-1-57506-033-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date auto-translated (link) - ↑ Hasel 1998, p. 194.

- ↑ Lemche 1998, pp. 46, 62: “No other inscription from Palestine, or from Transjordan in the Iron Age, has so far provided any specific reference to Israel... The name of Israel was found in only a very limited number of inscriptions, one from Egypt, another separated by at least 250 years from the first, in Transjordan. A third reference is found in the stele from Tel Dan – if it is genuine, a question not yet settled. The Assyrian and Mesopotamian sources only once mentioned a king of Israel, Ahab, in a spurious rendering of the name.”

- ↑ Maeir, Aren. "Maeir, A. M. 2013. Israel and Judah. pp. 3523–27, The Encyclopedia of Ancient History. New York: Blackwell".

The earliest certain mention of the ethnonym Israel occurs in a victory inscription of the Egyptian king Merenptah, his well-known "Israel Stela" (c. 1210 BCE); recently, a possible earlier reference has been identified in a text from the reign of Rameses II (see Rameses I–XI). Thereafter, no reference to either Judah or Israel appears until the ninth century. The pharaoh Sheshonq I (biblical Shishak; see Sheshonq I–VI) mentions neither entity by name in the inscription recording his campaign in the southern Levant during the late tenth century. In the ninth century, Israelite kings, and possibly a Judaean king, are mentioned in several sources: the Aramaean stele from Tel Dan, inscriptions of Shalmaneser III of Assyria, and the stela of Mesha of Moab. From the early eighth century onward, the kingdoms of Israel and Judah are both mentioned somewhat regularly in Assyrian and subsequently Babylonian sources, and from this point on there is relatively good agreement between the biblical accounts on the one hand and the archaeological evidence and extra-biblical texts on the other.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(tulong) - ↑ Fleming, Daniel E. (1998-01-01). "Mari and the Possibilities of Biblical Memory". Revue d'Assyriologie et d'Archéologie Orientale. 92 (1): 41–78. JSTOR 23282083.

The Assyrian royal annals, along with the Mesha and Dan inscriptions, show a thriving northern state called Israël in the mid—9th century, and the continuity of settlement back to the early Iron Age suggests that the establishment of a sedentary identity should be associated with this population, whatever their origin. In the mid—14th century, the Amarna letters mention no Israël, nor any of the biblical tribes, while the Merneptah stele places someone called Israël in hill-country Palestine toward the end of the Late Bronze Age. The language and material culture of emergent Israël show strong local continuity, in contrast to the distinctly foreign character of early Philistine material culture.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date auto-translated (link) - ↑ The Biblical Archaeologist, American Schools of Oriental Research, 1997, p. 35

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: date auto-translated (link). - ↑ Sparks 1998, pp. 96–97.

- ↑ FitzWilliam Museum, UK: Ancient Egypt.

- ↑ Smith 2002, p. 26.

Maling banggit (May <ref> tag na ang grupong "lower-alpha", pero walang nakitang <references group="lower-alpha"/> tag para rito); $2